Subscribe to our

How to Ride a Canoe In a Boiling River

A Calgary chemical engineer's unexpected journey with National Geographic Explorer Andres Ruzo to the Amazon and awe-inspiring Boiling River.

Stephen Hunt, Jan 23, 2026, Werklund Centre

Nyssa Ritzel has been a donor to Werklund Centre’s Explorers Circle since 2014, a program that always includes a bite to eat after a National Geographic Live show with the star Explorer.

What Ritzel, a Calgary chemical engineer, didn’t see coming was that it would lead to a trip of a lifetime that took her deep into the Peruvian Amazon jungle, but that’s what makes those National Geographic Live shows so memorable.

Once in a while, they change somebody’s life – and in January, 2025, somebody was Nyssa Ritzel.

“There’s always a dinner on Sundays after the show with four couples and four people from Werklund Centre,” Ritzel said. “And (Werklund Centre Transformation executive director) Greg Epton always asks (the speaker) great questions.”

Last January, the featured National Geographic Live speaker was Andres Ruzo, a geothermal scientist, teacher and science communicator who shared the story of his work analyzing, cataloguing and studying the Boiling River in the Peruvian Amazon jungle.

The day Ruzo appeared at Werklund Centre, Ritzel had to hustle to make it.

“We snowboard every Sunday, but we made it home to see that show,” said Ritzel.

What she heard that night over dinner in Werklund Centre’s Founder’s Room sounded like something from an Indiana Jones movie.

“Andres told us about the Boiling River, and when we said, 'Wow, it sounds amazing,' he said anyone who wants can come.”

As a chemical engineer, Ritzel had both the skill set – and tool set – that could contribute to Ruzo’s research.

She decided to take him up on it.

He agreed that she was a good fit.

“I was in charge of the flow team,” she said. But first she had to get there.

The Amazon jungle

Before he spoke at Werklund Centre, Ruzo, a Peruvian-Nicaraguan-American who is finishing his Ph.D at a university in Dallas, Texas, spoke to CTV Calgary’s Ian White, where he described the Boiling River when asked by White how it compares to Alberta’s own mountain hot springs.

“Ultimately, it’s a very similar process (to hot springs), but the key difference is the volume,” Ruzo said. “When you think of the Amazon basin, that watershed, it holds a tremendous amount of fresh water.

“Some would say up to 20 per cent of Earth’s fresh water is contained in the Amazon Basin.

“So what you’re looking at with the Boiling River is ultimately a super-charged hot spring as far as volumes of water go, because you’re looking at a river system that’s 6.4 km or almost four miles of thermal flow.

“And a lot of it is actually hot enough to kill you, amazingly enough.

“At its widest point, it’s about 30 feet wide, and at its deepest, it’s four and a half metres or roughly 15 feet deep – and that’s a lot of hot water.”

For Ruzo, who is part Peruvian, the Boiling River is a geological phenomenon tucked inside a cultural mystery.

“So much of the world hears ‘the Amazon’ and thinks, big scary spooky,” he said on CTV. “The snakes, the spiders, all that stuff. And they miss out on the point that the Amazon is really one of nature’s greatest celebrations of life on our planet.

“It’s unbelievable.”

Getting there

The first challenge for Ritzel was getting there.

Travelling to the Peruvian Amazon jungle meant a flight itinerary unlike any other – Calgary to Toronto to Bogota, Colombia, to Lima, Peru, where she met up with other participants including artists, photographers, a social media influencer known as Spooky Diver on TikTok, a PhD student studying stingless bees and others, including a German drone operator and a representative from Rolex, the watch folks, who sponsor Ruzo’s research trips.

From there, the group caught another flight to Pucallpa, a small Peruvian village at the mouth of the Ucayali River, which feeds into the Amazon, where they spent a night before going in a truck down an unpaved road into the jungle to experience the Boiling River.

“No lanes,” said Ritzel. “Mud. It was super-bumpy. We drove an hour and a half to the river, took a barge, then hiked 45 minutes to a part of the Boiling River that was cooler than the other parts – only around 50 degrees C.

“I fell in!” Ritzel said.

On CTV, Ruzo said bringing visitors to see the Boiling River and learning about Amazon jungle culture is an important part of trying to preserve it.

“I work in the communities there,” Ruzo said. “I have a goddaughter in one of the Indigenous communities there. And when I talk to my people down there, they say it’s weird because there’s history here, a history of – unfortunately – devaluing the jungle. Devaluing the cultures of the jungle, telling them that they are less than.

“So when you have local Amazonians see someone coming from the other side of the world to see their trees, they go, wait a minute: we’ve been told forever that the only value this jungle has is if it’s developed.”

‘Cool location’

For Ritzel, the appeal of the trip wasn’t just exploring the Boiling River – it was where the Boiling River was.

“It’s in a cool location,” she said. “There’s steam coming off the river.”

She said that usually, thermal water is related to mountains, as it is in Alberta and B.C., but the Boiling River is actually 400 kilometres from the closest mountain range.

The source of the geothermal water, it turns out, is related to oil and gas deposits nearby where oil companies have secured leases.

And then there was the jungle.

“Everything is alive in the jungle,” she said. “You can't sit on the ground. You can’t stand still because of mosquitoes.

“There’s snakes, bats and spiders everywhere.”

There were also monkey skulls on the ground, droopy-eyed sloths in the trees, and caimans (mini-crocodiles) along the river’s edge.

To really embrace an Amazon jungle retreat, you have to like spiders and snakes.

One morning, in the shower, Ritzel looked down by the drain to discover she had company.

“I had a pink-toed tarantula in my shower,” she said. “She was so cute – gorgeous.

“I like spiders.”

One of the best parts of the trip, she said, was the night hikes.

“We found tons of cool things at night,” she said.

One night, they found a black and white coral snake – and Ritzel thought it was cute, so she brought it back to camp.

“Turns out it was super-poisonous,” she said. “The locals were like, no! You need to get rid of that one!”

She said dinners were fun too, mainly because of the stories people told.

The locals were the Shipibo-Conibo tribe, an Indigenous nation of artisans known for using ayahuasca in spiritual healing chants.

Because of her chemical engineering experience, Ritzel was assigned the task of measuring the flow of water along the river.

"What that means is that there are three types of water,” she said. “Meteorological, metamorphic (squeezed out of stone) and Connate (from rocks and stone)."

Ritzel’s job involved understanding data as best she could – but the data was flawed, since the drones that filmed the Boiling River couldn’t accurately measure its depth.

In order to gather data, Ritzel had to load gear into a hard-carved canoe and go out into the Boiling River with Ruzos’ Ph. D advisor.

“You do flow measurements in canoes, tied on a string – and we sank!” she said.

The equipment did relay one important piece of data: the temperature of the water.

“56 degrees. Your skin is red after. It was hot in the water,” she said.

But luckily for Ritzel, as it turned out, the water was less hot than at other times of the year – and when it rained – which happened a lot – it cooled the Boiling River off enough for everyone to go swimming.

That led to fish swimming in the river, which would eventually get hotter and hotter until they were eaten by pink dolphins.

The stars in the sky

Another highlight for the travellers was the night sky, Ritzel said.

“The skies were crazy,” she said. “There was no light pollution. There were too many stars. Different stars than I’m used to (in the southern hemisphere).”

In his interview with CTV, Ruzo talked about how the Amazon jungle is receding as more and more of it gets developed for its resources – how it loses half a football field every minute of his life.

The way to help, he said, was to go there.

“You go there and it’s difficult not to fall in love with it,” he said.“That sticks with you, and you change and become an advocate for the jungle.”

For Nyssa Ritzel, that’s 100 per cent the truth.

“Would I go back? Yeah,” she said. “There are no mirrors. No cell phones. No internet.

“(All) we had was a pack of cards. It rains all the time. It’s super slippery. Everyone is hanging on to one another. You develop relationships.

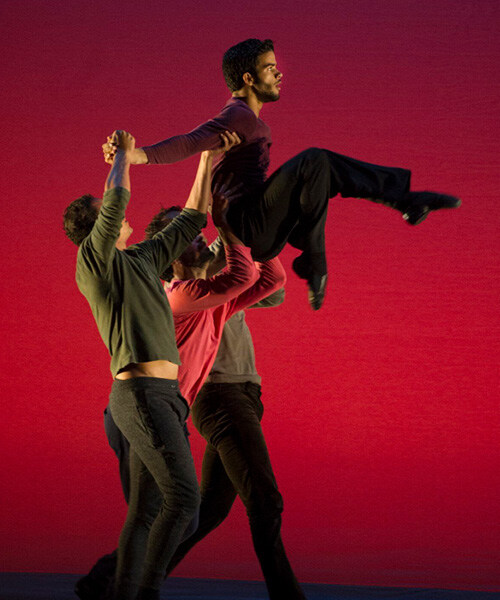

“People were very giving,” she said. “(They) take care of each other. We danced a lot. I sang a lot. Chanting. Used our creative side.

“Rain songs,” she said. “It was very beautiful.”

She is a huge fan of Werklund Centre and National Geographic Live.

Epton delivered her a gift basket for her baby and exposed a lifelong Edmonton resident to a part of Calgary she wasn’t really aware of.

“When I first moved from Edmonton, I thought there’s no arts scene in Calgary,” she said. “Not like (Edmonton’s) Whyte Ave. But there really is one!”

As far as National Geographic Live goes, it turns out she wasn’t a subscriber to the magazine growing up, and neither was her family – but now she buys four gift subscriptions for friends and family members.

As far as the Boiling River goes, she says she lost 12 pounds in two weeks – and why not an encore visit?

“When I did it, I thought, oh, once in a lifetime experience,” she said. “But now I’m thinking of going back again.”

Photos courtesy of Nyssa Ritzel

Stephen Hunt is a digital producer at CTV Calgary. He was a theatre critic at the Calgary Herald for 10 years and has reviewed Alberta theatre for the Globe & Mail since 2017.